Philip Johnson Interviewed by Susan Sontag

John Morgan-

-

- John Morgan for the Architectural Association, 2007

-

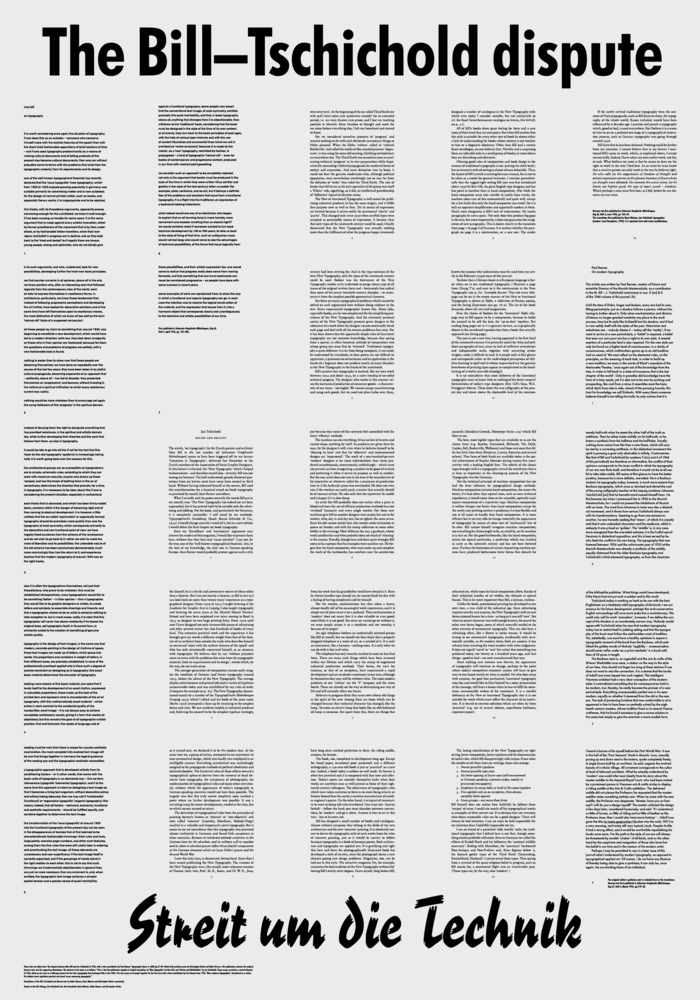

I can’t help but be seduced by Philip Johnson’s black-comic exchange with Susan Sontag — described by Marshall Berman as ‘pop nihilism in its most insouciant form’. As someone who was encouraged to do ‘good work’ and join hands with Geddes, Ashbee, Lethaby, Read, Mumford and co, I find Johnson’s honest amorality both shocking and refreshing. His voice resonates with self-mockery and self-delight. His candid disclosure offers one way to work and live in the modern world. In the absence of values, his pragmatic pick-and-mix vision offers an abundance of possibilities. ‘To be natural is such a difficult pose to keep up.’ (Oscar Wilde)

Charles Jencks places Johnson’s modern self-awareness under ‘camp’ — a sensibility Sontag knew a thing or two about. ‘I am strongly drawn to Camp, and almost as strongly offended by it. That is why I want to talk about it, and why I can. For no one who wholeheartedly shares in a given sensibility can analyse it; he can only, whatever his intention, exhibit it. To name a sensibility, to draw its contours and recount its history, requires a deep sympathy modified by revulsion.’ (Susan Sontag, ‘Notes on Camp’, 1964).

As the required result of this inquiry is a large-format print — perhaps encouraging ‘design as art’, just as Johnson appeared to encourage ‘architecture as art’ — I must not, as Sontag warns, be ‘too solemn and treatiselike’, or else I run the risk of producing an ‘inferior piece of camp’.

SS: … I think in New York your aesthetic sense is, in a curious, very modern way, more developed than anywhere else. If you are experiencing things morally one is in a state of continual indignation, and horror but [they laugh] if one has a very modern kind of —

PJ: Do you suppose that will change the sense of morals, the fact that we can’t use morals as a means of judging this city because we couldn’t stand it? And that we’re changing our whole moral system to suit the fact we’re living in a ridiculous way?

SS: Well I think we are learning the limitations of the moral experience of things. I think it’s possible to be aesthetic…

PJ: … I mean your moral approach is the [Lewis] Mumford one that you’re speaking about.

SS: Yes.

PJ: Patrick Geddes, the greatest good, and we must be good and do these things. That criterion leads you into what we have today, so we’ve retreated, or maybe advanced, our generation — if I can lift you up.

SS: Oh it’s nice of you [they laugh].

PJ: To merely, to enjoy things as they are — we see entirely different beauty from what Mumford could possibly see.

SS: Well, I think, I see for myself that I just now see things in a kind of split-level way… both morally and…

PJ: What good does it do you to believe in good things?

SS: Because I…

PJ: It’s feudal and futile. I think it much better to be nihilistic and forget it all. I mean, I know I’m attacked by my moral friends, er, but really don’t they shake themselves up over nothing?

SS: Well people do things.

PJ: Do they?

SS: Do accomplish things.

PJ: Do they? What have they done in New York City since the start? You read all the reports the other day in the paper — the chief man said you might as well spend your time writing to Santa Claus as talk about any possibilities of city planning in this city, and incidentally the English that are so good about morals and city planning, and have all these London County Councils and things they are so proud of, have ruined their city in the name of morality. Even worse than New York in this hopeless chaos…

After examining various Pop paintings in Johnson’s collection:

PJ: … Can we look at architecture, or do we always have to look at painting?

SS: No, no, we can look at everything, because it all fits together.

PJ: …[pointing to works] I’m a plagiarist man — you see, you must take everything from everybody — you see this is copied from Corbusier, that’s copied from Byzantine Churches — this is taken from Jaipur, India. This is, I don’t know, maybe this is original. It’s an underground house. We have some ponies grazing on the roofs, you see one come down to the water, but… it just shows you that at this very same time you’re doing one thing, you flip moods, you do something entirely different, quite opposite.

SS: But this is the very essence of modernity [PJ: Sure] in all the arts. I mean you see it even in somebody like Picasso [PJ: Yes, Picasso is rather…] he’s the first person who understood the principle of artistic plagiarism. [Goes to flowers]

SS: Yes — and these are real, real —

PJ: Real flowers — real, fake flowers.

SS: Real, fake flowers, of course.

PJ: You see the level of fakeness, that’s real [telephone rings] threedimensional [voice says hello] imitation, yes of an advertised meaning, and it’s those various levels of reality that make it all so fascinating…

© BBC, 1965. Quoted in Jencks, Modern Movements in Architecture, pp. 208–10