Oblique Points of View

Laurenz Brunner-

-

- Laurenz Brunner for the Architectural Association, 2009

-

The Italian architect Giovanni Lorenzo Bernini had ambitious plans for the entrance hall to the Vatican, which he designed in the 17th Century. Equestrian statues, sculpted angels and baroque ornaments were not enough for the grandness he envisioned. To elevate the entrance of the palace he used the theatrical trick of heightened perspective, which convincingly elongated the space. Even the Pope was pleased—if not for the unexpected side effect that people exiting the hall grew to giant proportions, whereas those mounting the stairs were dwarfed.

Medieval paintings typically scaled objects according to their spiritual or thematic importance rather than their physical proportions or relation to other objects. It was only in the 15th century that the geometric basis for perspective as we know it was established. At this time, a number of Renaissance painters began to experiment with intentional distortion and anamorphic perspectives in their work.

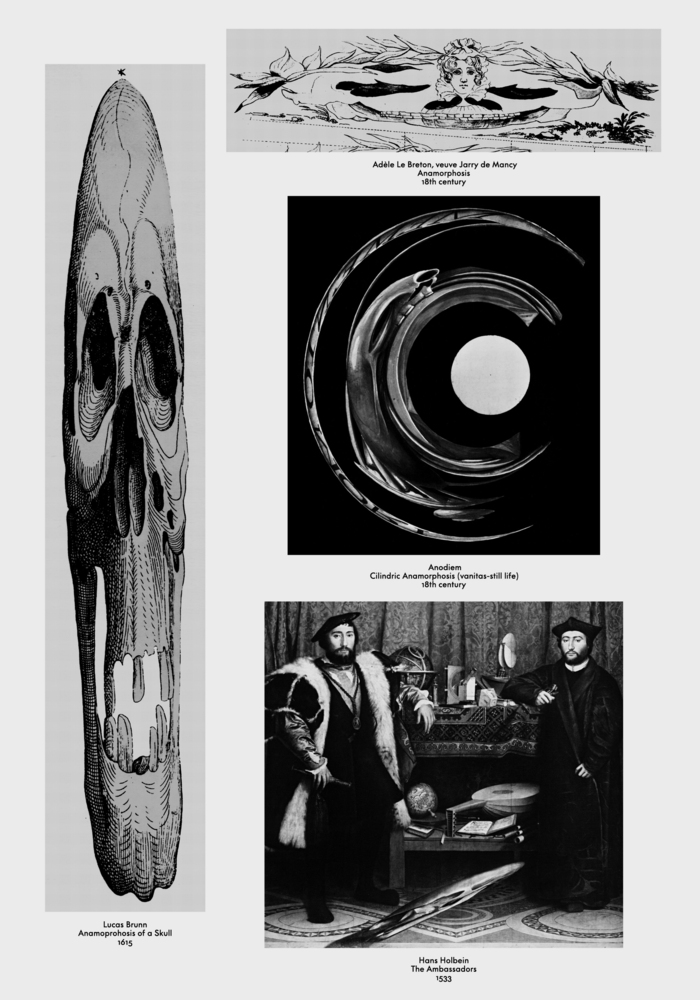

Anamorphosis is a term used to describe a distorted projection or design that reconstitutes itself only when viewed from a certain vantage point or when using a special device. The earliest works to use anamorphosis concealed secret images of disguised erotic or politically sensitive content. One of the most well known anamorphic paintings is The Ambassadors (1533), a double portrait by Hans Holbein, which contains a distorted skull hovering above the picture plane. It has been suggested that the painting was meant to hang in a stairwell, where the viewer would approach it from an oblique angle and see the ghostly forms morph into an accurate representation of a human skull.

Anamorphic elements do not only bend conventions of perspective, but also seem to stretch in both space and time. Like listening to a record alternating between 33 and 45 rpm, the content of such paintings unfolds itself to the viewer at different rates.

During the 17th century, Baroque murals often used anamorphic techniques to combine architectural elements with trompe l’oeil paintings. The “dome” and vault of the Church of Saint Ignatius in Rome is one of the most notable examples of illusory architecture. Due to complaints by monks about blocked light, an artist was commissioned to paint the flat ceiling to look like the inside of a dome, instead of actually constructing one. However, because of the ceiling’s flat surface, viewing the fake dome from the wrong direction produces the image of a rather alarming structural flaw.

While anamorphosis is seldom used in contemporary architecture, the technique recurs in the design of road markings that render arrows, words, and symbols legible from steep angles and high speeds. Have you ever stopped and tried reading the word S T O P painted on the pavement, or viewed abnormally elongated bicycle icons from directly above? Ignore the strange glances from passers-by as you stand on your toes in the middle of the road, attempting to bring things into focus. Perhaps you’ll have an indirect influence on their perspective, too.