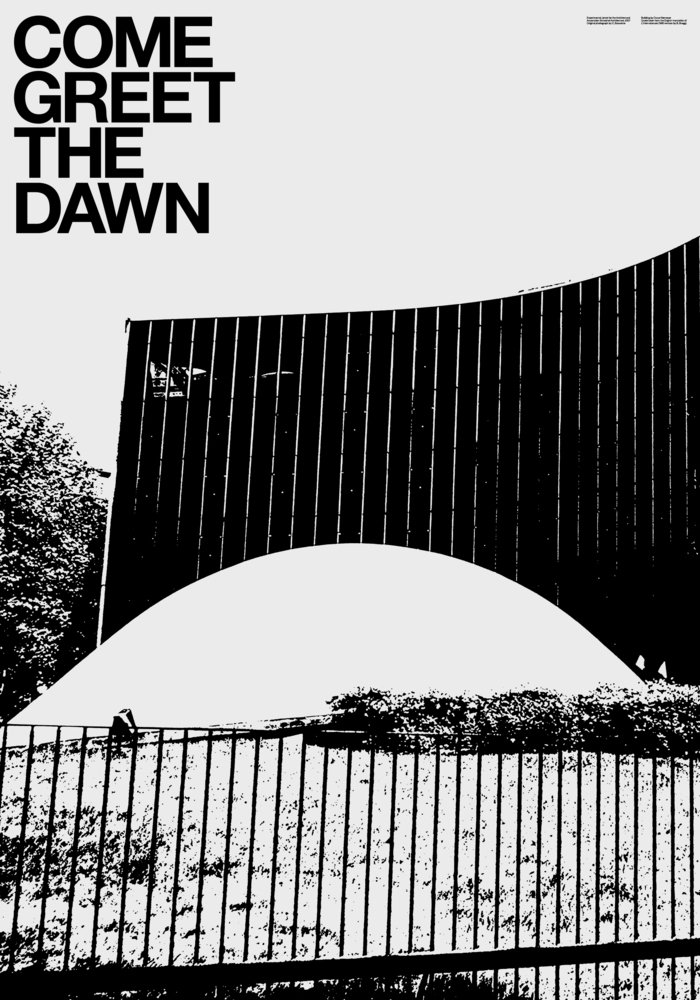

Headquarters of the French Communist Party

Experimental Jetset-

-

- Experimental Jetset for the Architectural Association, 2007

-

We knew about the existence of Oscar Niemeyer’s headquarters for the French Communist Party (built 1967–1972) for quite some time, but we became particularly interested in the building after meeting Armando Andrade Tudela, a Peruvian artist who is currently making a film about it. His enthusiasm for the building was contagious, so we have visited it a couple of times recently.

One of the things that we find particularly interesting about the building is its symbolic dimension. The idea of a symbolic modernism has always fascinated us, perhaps because it seems like such a paradoxical concept while in fact it’s not paradoxical at all. As Reyner Banham shows in his conclusion to Theory and Design in the First Machine Age, many modernist icons (such as Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona Pavilion) are highly symbolic structures.

Another seemingly paradoxical situation is the synthesis of symbolism and communism evidenced in the building. Again, there is actually nothing paradoxical about that: many commentators have pointed out that communism is loaded with religious imagery. Some even go so far as to suggest that communism is in fact a parody of religion, a farcical imitation of Christianity.

This latter stance is certainly something we disagree with. In our opinion, it’s the other way around: rather than regarding communism as a secular ideology appropriating religious concepts, we see religion as an illusory system appropriating secular matter, through rituals and mystification.

In that sense, we see symbolism as a secular, worldly construction, one that has more to do with the human psyche than with the world of gods and spirits. The symbolism at play in Oscar Niemeyer’s Headquarters for the French Communist Party is a constant reminder of that. Modernist symbolism, for a secular ideology.

-

-

- French Communist Party headquarters, designed by Oscar Niemeyer. Photos: Experimental Jetset

-

-

-

- French Communist Party headquarters, designed by Oscar Niemeyer. Photos: Experimental Jetset Photos: Experimental Jetset

-