Foreigners in foreign lands

Kasia Korczak-

-

- Kasia Korczak for the Architectural Association, 2008

-

As foreigners living in foreign lands, we are often asked to choose between national identities, despite the various terminologies of identification being skewed, if not altogether faulty. On the one hand, there is ‘immigrant’, implying, almost de facto, a desire for integration as the key determinant for success in a host country. On the other, there is the romanticised and somewhat passé term ‘émigré’, an evocation of whitened knuckles, gripping an increasingly fossilised sense of ‘home’. Either way, we lose.

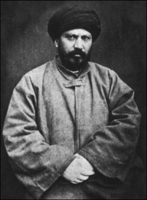

Instead we look to precedents. Some people have to blur, even betray, one identity in order to fight for another. In music, one could perhaps associate this conflict with performers like Bob Dylan or David Bowie. In Slavs and Tatars territory, it would be Jamal al-din Al-Afghani, Vladimir Nabokov, Attila the Hun or Aleksander (Eskander) Herzen.

We often sit around dinner tables and argue over which nations we like best and which the least. Responses vary widely but never fail to reveal a person’s politics and passions. A recurring trope – what has Australia really contributed to the world? – is often met by an equally clichéd turn to anti-Americanism. Regardless, we continue to excavate the intuitive, instinctive likes and dislikes of our childhoods (since smothered in our adult lives), and pummel them with the adulterated world of politics and culture. It’s like putting nature and nurture in a blender and making a smoothie called Know Thy Enemy.

While we debate the relevance of one national culture over another, we would do well to think of Lev Gumilev, whose theory of ethnogenesis entailed a rather moving and poetic, if not especially scientific, notion of ‘passionarity’. According to Gumilev, passionarity represents an ethnic group’s power source or vital energy. This energy undergoes an evolution through various stages: rise, development, climax, inertia, convolution and memorial. Russia’s uniquely European and Asian position, not to mention its tumultuous history, was seen as proof of its high passionarity. For Gumilev, Europe is in a state of inertia, or obscuration, and the Arab world is on the rise.

The Iranians would recognise this theory under another name – arbzadeghi (literally translated as westoxication) – perhaps one of the most important leitmotifs of the Iranian revolution, and central to the country’s subsequent theocracy. Garbzadeghi – literally meaning ‘struck by the west’ – refers to what some see as the corrosive effect western culture has had on the foundations of Iranian and Muslim society.

As with many ideas that deal with nationhood and ethnicity, Gumilev’s ‘Eurasianism’ has been hijacked: the Eurasia party today advances a worrisome breed of Russian nationalism. Today, to misquote Bono, we could say that Alexander Dugin stole this song from Lev Gumilev. We’re stealing it back.

-

-

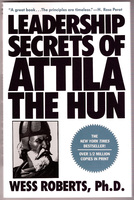

- Wess Roberts: Leadership Secrets of Attila the Hun

-

-

-

-

-

- Jamalal-din Al-Afghani

-

-

-

- Lev Gumiliev

-

-

-